FEB 24: Cool climate rice: How Kamenoo saved the north

FEBRUARY 2024

For February, there was an initial thought of flirting with love-themed or Utada Hikaru-themed sake (given the arrival of Hatsukoi “First Love,” this felt like a nice way to send love to our little monthly club) but many iterations later, things got geeky…and all of a sudden we were out of J-Pop phenom territory. Oops! Well, we can always revisit it later.

As Portland temperatures shifted from extreme cold to unseasonable warmth, the rabbit hole Molly and I were chasing took a similar turn. While Portlanders found themselves doing garden chores in late January, we began asking questions about rice agriculture, climate, and rice varieties. After all, 2023 was one of the hottest years on record in Japan, and during my October trip (rice harvest in Tohoku) I revisited the climate conversation over and over with sake producers, farmers and rice growers. Extreme summer heat caused droughts even in water-rich Japan, but moreso it stressed plants to such a degree that they stopped respirating to conserve moisture. This means that when it gets too hot, plants simply stop growing (converting oxygen to ATP) and ripening. So if a plant requires, lets say, 120 days to ripen, it’ll need to make up that growth time at the end of the season– as long as Autumn storms don’t interfere.

This is the cultivation window: that span of time between Spring and Fall when conditions are favorable to rice growth. In cold Northern Hokkaido, the window is short: it starts around the 135th DOY (May 15) and ends around the 280th (October 7th). All growth must start and end within this window, or else the weather will be too cold. Compare this to southern Kagoshima, whose window is from 80-305 DOY, or March 21 to Nov 1. That’s a much larger window. In the north, you want cold tolerant rice that ripens quickly. In the south, you want rice that is heat tolerant and ripens slowly.

Japan’s record heatwaves are flipping the script on a century of rice breeding for cold tolerance. From the 1600s to as late as the 1950s, a majority of Tohoku and Hokkaido residents were in a state of extreme poverty, growing more desperate in years of bad weather and volcanic activity. The majority of Japan’s great famines occurred in Tohoku, which was only barely warm enough to ripen rice in a good year. For Tohoku farmers, rice was not grown for sustenance (too valuable!) but as currency. Cold-tolerant grains suited to the northern region (buckwheat, barley, millet, foxtail millet) were staples for the masses, while rice was grown almost exclusively for landlords & taxes (between 60-75% of the total harvest). Combined with government and private ownership of forest tracts which prohibited villager hunting and foraging, Tohoku residents lived on the knife-edge of starvation most of the year. Populations– mouths to feed– were managed largely through infanticide, and when that was outlawed in the late 1800s, the simultaneous rise of urban centers led desperate parents to contract their children to factory, mining, and brothel operations. It’s because of this long and sordid history that the Northern population density remains low, even today.

From the 1800s to the 1930s, peasant revolts did happen, particularly in times of famine, and particularly in Tohoku. But in general, these systemic challenges: rice as currency, landlordism, high taxes, were seen as an unfortunate fact of life that one must accept and submit to. Revolutionary efforts tended to fizzle out because of the strong conservative and paternalistic values among peasants (blame the landlord for failing to take care of their subjects, not the system) + cultural disapproval toward social disruption. For the most part, improvements in quality of life would need to happen gradually, scientifically.

Cold hardiness was key. But in 1800s Japan, breeding efforts were slow and incidental. The observant and well-resourced farmer might retain a few seeds from a particularly strong plant, hoping it would grow well the next year. But even as early as the Edo period, most rice seeds were sold by landlords and governments to farmers on credit, stifling individual breeding efforts. Farmers were trapped in cyclical debt, and could not retain their own seeds.

This critical work of selective breeding was, therefore, extremely difficult but not impossible. In 1893, the farmer Kameji Abe of the farming village Amarume in the Shonai Plain of Yamagata noticed a few stalks standing after a Summer cold snap that decimated one village’s fields. Even among the cold-tolerant varieties known at the time, these stalks were the lone survivors. Abe then bred and propagated these grains, soon developing the very first variety of highly cold-tolerant, early ripening, high yield and also flavorful rice identified in Japan: Kamenoo, Turtle Tail. Its combination of characteristics made it ideal for Northern farmers, allowing production to rapidly reach a height of >200,000ha in 1925.

“Kamenoo in the west, Omachi in the east”: these mother varieties were the first of their kind but shared similar weaknesses, being sensitive to both pests and pesticides, tall and prone to wind/weather, and eventually– incompatibility with combines, as they need to be hand-harvested. Kamenoo was succeeded only by its progeny, Rikuu-132, and after that a huge family of cold climate successors both for eating and brewing. Almost all rice varieties grown north (west) of Tokyo today descend from Kamenoo!

After decades of absence, in the 1980s Kamenoo was resurrected from obscurity but not for eating, for brewing. The public was inspired by the popular manga Natsuko no Sake, whose hero endeavors to make a junmaishu from Kamenoo in an era of brewing defined by Yamadanishiki rice and arutenshu (alcohol-added). This brought Kamenoo into the public vision and since then, committed (and slightly crazy) brewers have sought it out for small and special releases.

Those who did not subscribe to the Sunflower Sake Club in June 2023 will receive a 300ml bottle of Senkin Junmai Daiginjo Kamenoo; those who did, will receive an alternate (described below).

Source: Genome-Wide Comparative Transcriptional Analysis of Developing Seeds among Seven Oryza sativa L. Subsp. Japonica Cultivars Grown near the Northern Limit of Rice Cultivation

Kamenoo was an incredibly important first step toward solving the hunger and poverty in Tohoku and Hokkaido. It took an embarrassingly long time for Japanese politicians, urbanites and Emperor alike to prioritize rice breeding research, putting the full weight of the government behind this work, but the research that succeeded Abe would eventually lead to Rikuu-132 and many hundreds of viable progeny in the decades to come. In the above family tree for Hokkaido rice, Rikuu-132 is in the first column on the left, third from top, the parent for almost all varieties that follow.

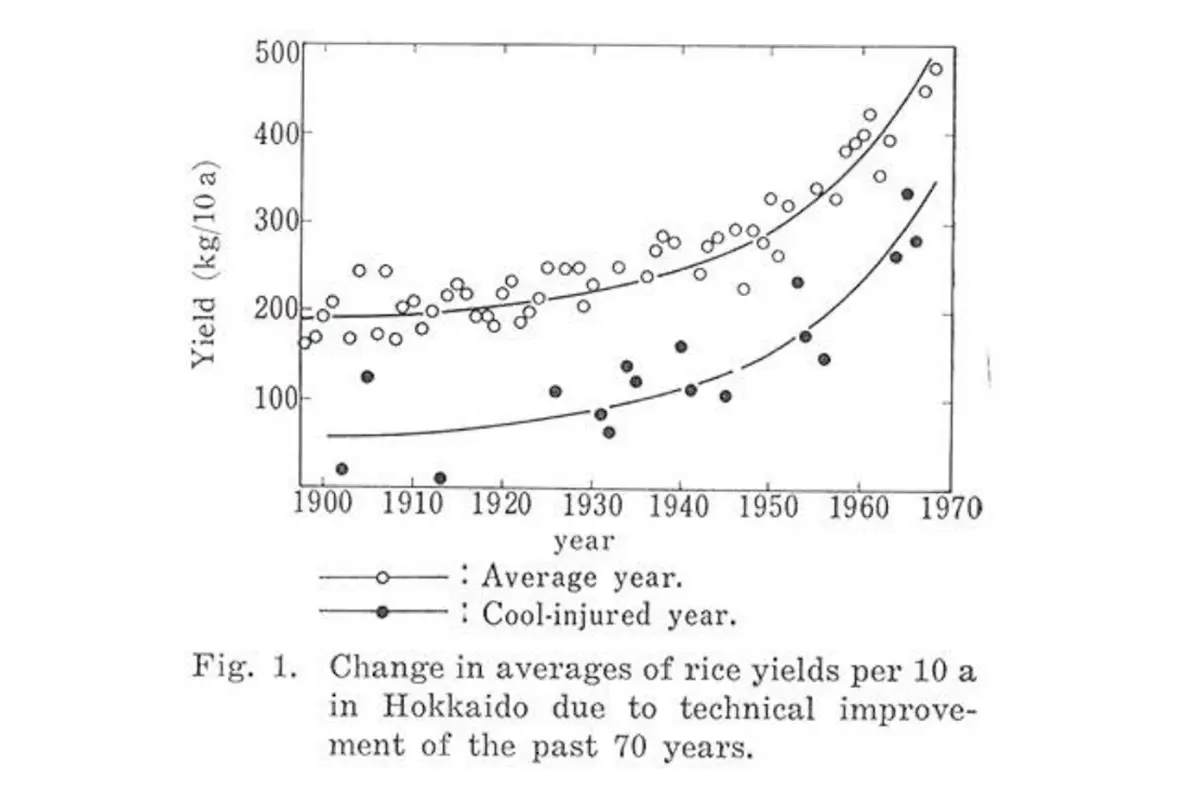

At last, rice that would sprout, ripen, and could be harvested in the short Northern growing season had arrived. In the below chart, you’ll notice that from 1920 to 1930 rice production leapt from 20% to 30% of Hokkaido’s cultivation area. Further improvements to yield and resistance to cold injury made the extreme famines, zero and near-zero as shown in the graph on left, a distant memory. Even in cold years, yields were adequate. By 1965, cold yields surpassed average yields from 1900. At this time the Japanese Economic Miracle, advancements in industry and research, smallholder land ownership and huge improvements in individual quality of life, gave Tohoku citizens– perhaps for the first time in history– the luxury of 3 bowls of rice each day. A rare treat–perhaps twice a year– for most late-1800s Tohoku tenant farmers.

Source: Research on Cool Injury of Paddy Rice Plants in Japan, Satake T.

Where the above graph ends, 1970, Japan reached a turning point where for the first time in history rice supply exceeded demand. Breeding was a wild success Government initiatives were then introduced to subsidize the fallowing of fields, with particular attention to regions with subpar quality such as Hokkaido. 1969 is an inflection point in the chart: 50% of cultivation area, to 45% the following year, down to 30% in 1990.

Source: Agriculture in Hokkaido (Second Edition, 2009), Sapporo University

Breeding efforts quickly turned to quality. With Koshihikari as the gold standard for eating, and Yamada Nishiki as the gold standard for brewing, breeders focused on flavor, consistency and ease of cultivation (such as seeding directly into the field). In 1956, Niigata introduced gohyakumangoku: a 3rd generation offspring of Kamenoo and 2 generations from Omachi. Gohyakumangoku is a reference to the record 5,000,0000 koku (a unit of rice) that had been grown that year. Suited to cool climates, gohyakumangoku quickly became the pride of snowy, mountainous Niigata and its light, delicate flavor paved the way for Niigata’s clean and dry tanrei karakuchi style. Koshi no Kanbai, a famous brand from Niigata, is credited with starting the jizake (local sake) boom in the 1970s and making Niigata sake the new “it” style, following the sweet bulk brews of the post-war years.

Miyamanishiki, fellow Kamenoo offspring, was Nagano’s attempt to take on Niigata. Using the novel gamma radiation breeding techniques of the era, Miyama Nishiki was discovered and introduced in 1978. Its cold and elevation tolerance make it especially suitable for not only Nagano, but the rest of Tohoku, where it is cultivated widely.

The master brewer at Daisekkei Sake Brewery, Mamoru Nagase, described Miyama Nishiki as follows: “Miyama Nishiki has a hard rice quality that makes it difficult to dissolve in the moromi (fermentation mash). As a result, the sake tends to have a clean, light taste and sharpness.” This is a characteristic shared by most cold tolerant rice, and is becoming such a desirable characteristic for fresh, modern sake that some warm-climate breweries specifically seek it out.

February’s miyamanishiki selection, Chikuma Nishiki’s “Kizan Sanban” is made richer as a genshu (undiluted) namazake (unpasteurized) whose fermentation is halted at 15%, to retain a bit of natural sweetness. The density (-15 SMV) and viscosity compliments the intrinsically light character of fresh miyamanishiki, making for an indulgent and complex brew. This batch is its inaugural entry into the Portland market and a lovely late-Winter, early-Spring treat.

We now approach “modern” rice: that is, rice developed in the last 40 years. Out of a desire to replace Miyamanishiki with something unique and local, the Akita prefectural research association began research and development in 1983, finally recommending Ginnosei for ginjo brewing in 1992. Ginnosei lacks a clear shinpaku (white starchy heart) and is a bit harder to grown than Miyamanishiki (slightly less cold resistance, poor bacterial blight resistance), but yields are good, grains are large, and protein content is relatively high, which produces additional umami (amino acid content) in the finished sake. Most important, it’s very easy to polish down to 50-60%, as it resists cracking in milling and in soaking. Akita Sake Komachi (developed after) took its place as the premiere Akita rice, but Ginnosei is still loved on a bit of a culty level and tends to be more affordable as well.

Source: Sake rice family tree, Toshio Ueno, 2016

Finally, for those club members from July, we have a 200ml sake made from Hokkaido Ginpu rice, by a brewery in Aichi prefecture: Shibata Shuzo. Like all northern rice, Ginpu is appreciated for its lightness and delicate character, and since Shibata Shuzo brews with exceptionally soft well water, the two characteristics are a good complement.

Source: Hokkaido Rice Board website

Like Aichi, Hokkaido set out to develop its own rice varieties, for sake and for eating. In so doing, it could build brand recognition and a sense of locality around. That research began in the 70s and has been ongoing since. Ginpu, registered in 2002, was the first sake rice to earn Hokkaido recognition and is now among the top 10 most widely grown sake rice varieties as well as being in demand throughout Japan. Climate change is absolutely to thank for Hokkaido’s recent successes, but Ginpu, and later Suisei and Kitashizuku, are working in tandem. Along with Joiku, Hatsushizuku and Kirara (distant Kamenoo offspring), warm-climate varieties Omachi and Hattannishiki form the basis of Hokkaido’s rice.

As the climate warms, the landscape of Hokkaido and Tohoku will change. We all wonder what the future holds for us, but the excitement around Hokkaido and Tohoku sake in the last 30 years, its near-constant reign in competitions and sales statistics, is one portent of sake’s future. At least we can know that much!

COOL CLIMATE RICE:

THE SAKE

Chikuma Nishiki “Kizan Sanban” Junmai Ginjo Genshu Namazake (720ml)

Notes of pfeffernusse, candied aniseed, peach rings, wintermint, green apple, coconut water, full body and lingering sweetness.

- Location: Saku City, Nagano: south of Komoro & Karuizawa

- Style: Junmai Ginjo Genshu Namazake

- Rice: Miyamanishiki (Nagano)

- Polishing: 55%

- Yeast: secret

- Water: 4 different wells drawing from the Chikuma river, all soft

- ABV: 15%

- Acidity: 3.0

- SMV: -15

Storage: refrigerator, enjoy within 6 months of receipt.

Service: lightly chilled, ice cold (mutes the sweetness), or heated to ~140F. You can also try infusing the sake once it’s hot with a piece of lime or lemon peel, stirring for 15 seconds before enjoying.

Pairing: citrus, radicchio and fennel salad; lemon & olive oil cake; honey-drizzled cheese on toast (something a bit creamy and tangy: goat, delice de bourguignon, fresh sheep’s cheese), creamy coconut-based curries.

Akitabare Nama Honjozo “Shunsetsu: Spring Snow” (720ml)

Light and delicate, like mineral water with a squeeze of lime; gently floral and grassy on the nose, but with subtle bass notes of cashew, brazil nut and cheesecake on the palate that become more prominent ~10-12 months after bottling. A tiny bit of mineral astringency on an otherwise very crisp finish.

- Location: Akita City, Akita

- Style: Honjozo Namazake

- Rice: Ginnosei

- Polishing: 65%

- Yeast: Akita Konno #12

- Water: soft well water

- ABV: 14.5%

- Acidity: 1.4

- SMV: +3

Storage: refrigerator, endeavor to enjoy within 12-16 months of bottling

Service: anywhere along the spectrum! Lovely ice cold, light chill, room temp, gently warmed, and even hot. My favorite sake for infusions (citrus, ume, mushrooms, fish fins, tea!) because it serves as such a great canvas, complimenting other flavors without overpowering them.

Pairing: very, very versatile. My go-to for Russian food (think cold appetizers, charcuterie and cheeses, deviled eggs, dried and cured fish, dilly salads, CAVIAR!) because it reminds me of the ice-cold vodka my Russian family always had on the table, except…less boozy! With that said, equally delightful with any kind of Spring food but especially vegetable-inspired dishes: fresh peas, green garlic and watercress; Six Seasons’ celery, mint, and almond salad; and of course, just about any delicate Japanese fare, including daikon nabe, sushi, sashimi and vegetable sides.

EITHER:

[If you were NOT a member in July 2023…]

Senkin Junmai Daiginjo “Modern:Kamenoo” (300ml)

Bright, elegant, delicate and aromatic: notes of peach, orange & orange blossom, rice krispies, with a light touch of bitterness on the finish.

- Location: Sakura, Tochigi

- Category: Junmai Daiginjo Muroka Genshu

- Pasteurizing: Bin hi-ire, namazume (single pasteurized in a hot bath)

- Rice: organic Kame no O (local to within 5km of the brewery)

- Polishing: 40% / 50% (koji/kakemai)

- Yeast: Tochigi (proprietary strain)

- ABV: 16%

- Acidity: 2.2

- SMV: -2

Storage: refrigerator

Service: lightly chilled to room temperature is my favorite, cold and I felt it was almost too light, unable to express the complex flavor profile.

Pairing: Tomatoes with Tosa Vinegar (recipe follows), yuzu kosho rice (cook white rice, stir in yuzu kosho at the end, top with a tiny drizzle of olive oil!), sunomono, sauteed spring peas with mint, cucumber-cream cheese-dill tea sandwiches, picnics!

OR

[If you WERE a member in July 2023]....

A really wonderful balance of whipped cream and mochi notes balanced against just-ripe green melon, rainier cherry and those little Dole/Del Monte fruit cups so many of us grew up with. Light-hearted and light bodied with a mouth-coating silky softness.

- Location: Okazaki City, Aichi

- Category: Junmai Ginjo

- Pasteurizing: Once

- Rice: Ginpu (Hokkaido)

- Polishing: 60%

- Yeast: #1801

- Water: Kanzui, God’s Water: sourced from a 60 year old well hand-dug a short ways up the mountain. One of the softest brewing waters in all of Japan.

- ABV: 15%

- Acidity: 1.5

- SMV: -3

Storage: Cool & dark (65F or less ideally)

Service: fridge to room temp; warmed to ~120F can be really pleasant too. The soft sweetness of the rice comes up while the fruit notes mellow out.

Pairing: sweet mochi, cheesecake, cream cheese (esp. nut & dried fruit cream cheese balls…you know the ones), cucumber- cream cheese (or vegan CC!) & dill tea sandwiches, whipped cream & fruit sandos, socal-style puffy fried fish (or tofu) tacos, backyard cookouts, fresh crab salads & nigiri, cherry blossom watching & general picnicking!