MARCH 2024, The Great Old Ones (Shichi Hon Yari & Mimurosugi)

Sunflower Sake Club, March 2024:

The Great Old Ones

The earliest mentions of sake come from the ancient texts the Kojiki ~(711 AD) and the Nihon Shoki (720), which chronicle sake’s place in mythology as well as Imperial courts, ritual, and religion. During this period sake was primarily for use in religious ceremony, bearing the term omiki sake. In the Fudoki (~730 AD), sake is described as coming from rice and (koji) mold, a technique imported from China. By the late Nara period (710-784 AD) the use of koji was well established and these early sake, more accurately thick and ricey doburoku, were enjoyed ritually, recreationally and medicinally by the court and its priests.

When the court moved to Heian-Kyo (modern-day Kyoto) from the period 794-1185 an intensive period of artistic and cultural development began within the network of aristocrats that surrounded the emperor. Court poetry, religious iconography, art and performance, became the daily practice of idle nobles. Sake production moved to shrines and temples and in diaries from this period the most affluent nobles drank sake on a daily basis. Murasaki Shikibu, the famed courtesan author of The Tale of Genji, criticizes the men of the Heian courts, calling them “drunken men who make obscene jokes and paw at women.”

In the 13th century, power shifted from the Imperial seat to military dictators, shogun, who would dominate politics for the following 600 years. Along with this change, old traditions were upset and the nobles lost their exclusive access to sake. The methods of sake production were adopted by small commercial operations, and by 1425 Kyoto had 387 licensed breweries. Sake was still a luxury good, but a luxury good accessible to merchants, town chiefs and money lenders, rather than just nobility. Around this time (~1200-1500) the buddhist monks at Shoryakuji temple (est 992) in Nara were hard at work developing sake brewing techniques. Multi-stage addition, starter mash (moromi), the use of polished rice for both koji and mash, and even pasteurization, are among the technologies invented by monks or adapted from Chinese knowledge. Due to the extraordinary size and scope of the Shoryakuji temple campus (86 subtemples!), and the competitive financial and political climate, the temple fundraised in part by selling sake. The ninth shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, Ahikaga Yoshihasa, gave this monk sake, shoboshu, a ringing endorsement, saying that Shoryakuji sake was “simply the best.”

This is the tumultuous historical context of medieval sake production and the focus of your March 2024 club pack. Time travelers, read on…

Mimurosugi Tokubetsu Junmai, “Dio Abita”

Imanishi Shuzo, Nara, est. ~900 AD (1660)

Imanishi Shuzo: The History

Nara is considered the actual birthplace of sake in Japan (as opposed to the mythological birthplace in Shimane), and within Nara Mt. Miwa is sake’s specific place of origin. Mt. Miwa is tremendously important in Japanese culture as it played a central role in Japan’s origin story. Long long ago Omononushi helped Okuninushi unite the kami (gods) of earth, and to repay him, Omononushi was given Mt. Miwa to embody and reside in. On top of the mountain you’ll find Omononushi’s shrine, Ohmiwa, which is the oldest shrine in Japan. Ohmiwa Shrine and Mt. Miwa are so sacred that for a long time, regular people were forbidden from access.

Omononushi is also considered a patron god of sake brewing, and as a result many alcohol producers in Japan make an annual pilgrimage here to pray for a successful year. The front of the shrine is lined with tributes (barrels of sake, casks of whiskey) and eggs, in consideration of Omonononushi’s serpent form. Every year on November 14th Ohmiwa Shrine hosts a sake festival with dances, prayers, tasting, and the unveiling of a giant “mother” o-sugidama (ball of cedar boughs) 6 ft wide. Ohmiwa Shrine is where sugidama originated, and have since gone on to serve as a universal symbol for sake. Sake traditionally offered to deities, omiki, was originally read as “miwa,” and makura kotoba (the poetic epithets used in Japanese ancient poems) for the word “miwa” is read as “umazake,” which means “delicious sake.”

Why do the clouds hide Mount Miwa so– that lonely threshold?

People are what they are, but how I wish clouds at the least would show their kindness.

Princess Nukata / composed in the latter half of the 7th century

On Mt. Miwa but beneath Ohmiwa there’s a small shrine which is the only one of its kind in the world. Takahashi Ikuhi no Mikoto, an ancient toji, is enshrined here: he is considered the first master brewer of Japan. According to the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, in ~200 AD Ikuhi was deified for saving Nara by appeasing an angry god (Omononushi) with his delicious sake. A plague had laid waste to the region and as part of his plan to convince Omononushi to stop the plague, Emperor Sujin (10th emperor of Japan) commissioned Takahashi to brew the most delicious sake in the world by the following day. He did so, and this sake became a favorite of Omononushi, who ended the plague. Takahashi was rewarded by being enshrined at the foot of Mt. Miwa.

It’s here at the foot of Mt. Miwa that you’ll find Imanishi Shuzo. Written records go back as far as 1660, but it’s known that Imanishi Shuzo existed long before that– even if those records are lost. Using the water from Mt. Miwa as well as rice from the surrounding area, 14th generation Imanishi-san subscribes to a philosophy of “pure and correct” brewing: not with respect to efficiency, but to preserve the essential elements of brewing as a sacred practice. Out of respect for their place of origin, as well as the fact that Imanishi Shuzo was founded as an omikigura– a brewery that produces omiki, ceremonial sake– purity is hugely important. The brewery is cleaned thoroughly every day, steamed rice is hand-transported through the facility, rice is air dried and hand-washed in tiny batches, as if to intimately reflect the pinnacles of Shinto practice: cleanliness, purity, reverence, proper and correct procedure.

As far as records are concerned, Sudo Honke in Ibaraki Prefecture, dated to 1141 and 55 generations deep, is the oldest brewery in Japan. But Sudo Honke refuses this title. In a 2015 interview with japanese magazine Shukan Asahi, the 55th head of the brewery, Yoshiyasu Sudo, said that Sudo Honke wasn’t the oldest sake brewery in Japan. “It’s a brewery in Nara, not us,” apparently referring to Imanishi Shuzo. In response, Imanishi-san comments that “we can only list our founding as 1660 because that’s as far back as we can trace it” with physical proof. “We’re certain it goes back further, but we can’t say that unequivocally.” Furthermore, there are no surviving records of why the brewery was created– very unusual for breweries of this period.

Imanishi Shuzo is also one of the 8 official, sanctioned producers of bodaimoto sake in Nara, preparing one batch of (official) bodaimoto per year from the mother starter grown by Shoryakuji temple in Nara. Bodaimoto is a fermentation starter method developed by monks at Shoryakuji in ~1200 AD, and after falling into obscurity for a century or more, has been readopted by Shoryakuji for participating breweries in Nara. Every year, the Shoryakuji monks work with brewers to prepare one “mother” batch, which is then divided among participants. Each brewer takes their portion, going on to propagate the starter into a full batch. This sake is not imported, but worth seeking out the next time you’re in Japan.

Dio Abita: The Sake

Dio Abita, which translates to “God Dwells” in Italian, is a reference to the omnipresence of Omononushi-sama in Mt. Miwa. This is Imanishi Shuzo’s message to the world: that their brewery is born from the divine history of Mt. Miwa, brews sake from its water, rice and traditions, and works in a manner representative of Shintoism: purity, cleanliness, intentionality. The sake itself is modern in style, with moderate alcohol (13%), crisp fuji apple and pear notes, a bit of cherry icee and ramune soda, and a sort of delicately savory, carrot sweetness, overall reading very clean and pure.

Imanishi Shuzo achieves such a lovely balance at 13% alcohol by extending the fermentation from the usual ~20 (for a junmai) or ~30 (for a ginjo) to over 40 days at a very cold temperature. This low and slow fermentation slows the breakdown of rice and the production of alcohol so that the finished product is much lighter than most sake. In other words: super sessionable and easy to drink, but not without sacrificing subtle complexity.

Stats

- Rice: Yamadanishiki (locally grown)

- Rice polishing ratio: 60%

- Other: Muroka (not charcoal fined), genshu (undiluted)

- Yeast, SMV, Acidity: undisclosed

Dio Abita has remarkable temperature versatility, being fantastic warm and hot, chilled or room temperature. Heated, it gives off apple cider vibes; chilled, it’s light and refreshing with a delicate touch of effervescence. Scallop and apple tartare, melon & prosciutto, endive canapes with strawberry and goat cheese, zaru soba when the weather warms, or houba yaki (sweetened miso grilled over coals, enjoyed as a sake snack or topping for other items.

Shichi Hon Yari Junmai Namazake, “Seven Spearsmen”

Tomita Shuzo, Shiga, est. 1543 AD

Tomita Shuzo: The History

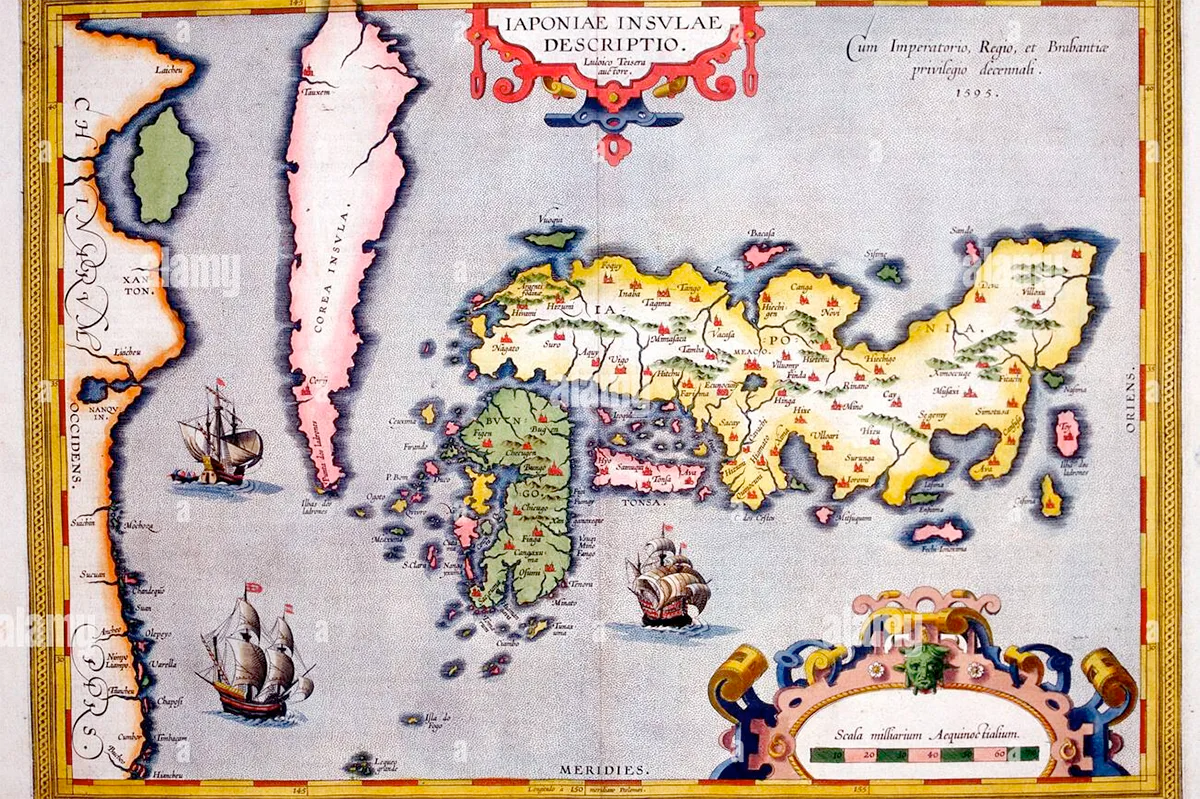

It’s the year 1543 AD in the Gregorian calendar; Tenbun 12 in Japan. King Henry VIII has allied with Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, against France. Under the reign of sultan Suleiman the Magnificent the Ottoman Empire is continuing its dramatic growth, now into Hungary. Nicolas Copernicus publishes On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, and Szechuan province receives its first chili peppers from trade with the Spanish and Portuguese. In the land that will become North America, the last bands of Athapaskan-speaking people are migrating from today’s Western Canada to the American Southwest, to join the Navajo and Apache tribes established by their forefathers almost 700 years prior.

In Tanegashima Portuguese traders blown off course have made first European contact with the Japanese; they bring guns and Christianity. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who will go on to become one of Japan’s “Great Unifiers,” is born in Aichi. And in Kinomoto-cho, present-day Nagahama City, Tomita Shuzo is established.

Kinomoto-cho is a convenient location at the intersection of the Hokkoku Kaido (northern highway) which connects Niigata to Kyoto. The Hokkoku Kaido isn’t one of the 5 primary ancient highways, but it’s still a very important route. Buddhist pilgrims bound for Zenkoji temple in Nagano, gold miners bound for Sado Island in Niigata, and diplomats traveling between castle outposts pass through regularly. Here, an ancient buddhist temple features one of the tallest buddha statues in Japan and the streets are filled with inns and high class accommodations for samurai and court nobles. The ground is flush with limestone-rich water from Mount Ibuki, the region is famous for rice production, and the freshwater fish from the enormous Lake Biwa are highly sought after, unique to this region. It’s a busy and auspicious site for a sake brewery.

In 1543 the Tomita family begins sake production. The brewery enjoys success in its early years but it’s not until 1584 that Shichi Hon Yari, Seven Spearsmen brand, is born.

Many of Japan’s most famous stories and historical figures come from the tumultuous Sengoku (Warring States) period that ran through the 15th and 16th centuries. During this time, ruling power was constantly in flux as regional daimyo vied to rule Japan as Shogun: military dictators. Toward the end of the Sengoku Period, the Battle of Shizugatake served as a decisive battle in the eventual victory of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Oda Nobunaga’s death had left a power vacuum, his generals siding with different sons. In June of 1583 Toyotomi Hideyoshi seized an opportunity, marching his troops 50 miles overnight in a surprise counterattack against opposing forces at Nagahama Castle (in Kinomoto). Among Hideyoshi’s forces were seven generals, later called the Seven Spears of Shizugatake. Under the impression Hideyoshi was occupied in faraway Gifu, the defense was caught off guard, losing the castle and retreating to its headquarters in Fukui. Hideyoshi’s forces pursued, and this castle was lost, too. Seeing their position , the defeated general committed seppuku along with several others. This victory ultimately led to Hideyoshi’s consolidation of power and was among the final challenges of his rule.

Many of Japan’s most famous stories and historical figures come from the tumultuous Sengoku (Warring States) period that ran through the 15th and 16th centuries. During this time, ruling power was constantly in flux as regional daimyo vied to rule Japan as Shogun: military dictators. Toward the end of the Sengoku Period, the Battle of Shizugatake served as a decisive battle in the eventual victory of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Oda Nobunaga’s death had left a power vacuum, his generals siding with different sons. In June of 1583 Toyotomi Hideyoshi seized an opportunity, marching his troops 50 miles overnight in a surprise counterattack against opposing forces at Nagahama Castle (in Kinomoto). Among Hideyoshi’s forces were seven generals, later called the Seven Spears of Shizugatake. Under the impression Hideyoshi was occupied in faraway Gifu, the defense was caught off guard, losing the castle and retreating to its headquarters in Fukui. Hideyoshi’s forces pursued, and this castle was lost, too. Seeing their position , the defeated general committed seppuku along with several others. This victory ultimately led to Hideyoshi’s consolidation of power and was among the final challenges of his rule.

Shizugatake Mountain lies just west of Kinomoto city limits, a steep peak 421m in elevation that overlooks all of Lake Biwa. This mountain and the surrounding city was made famous in the aftermath of the battle, and Tomita Shuzo– an enterprising local brewery– seized the opportunity to brand its sake in honor of the victors. Shichi Hon Yari: Seven Spearsmen sake was to be the chosen brew for samurai and villagers celebrating the new leader of Japan.

Shichi Hon Yari: The Sake

The tiny Tomita Shuzo, founded 1543 but rebuilt in the 1700s, is essentially the size of one large living room. Equipment is shifted in and out of the room’s corners as needed and all sake is essentially handmade. The 15th generation president is also the toji, and succeeded a line of Noto Toji before him, who established the brewery’s fuller-bodied style. The mineral-rich water from Mt. Ibuki contributes to this character and fortifies the sake with richness and umami. In the early 20th century, famous artist Kitaouji Rosanjin was such a fan of Shichi Hon Yari that he traded art as payment to cover his perpetual tab, even carving the wooden sign that hangs above the front door, and which is recreated on this sake’s label.

This unpasteurized, fresh namazake is available for a short period each year, and is brewed with Shiga’s local Tamazakae rice, a close relative of the heirloom grain Wataribune. It has a bright, yeasty, biscuity nose, fresh and herbal flavors, rich body, and a sharp clean finish. On the green side I get notes of sea lettuce, fresh sweet pea shoots and sweet fennel; on the other hand, there’s banana, white chocolate and grapefruit. This nama is fantastic with the flavors of Spring: fresh watercress salad with goat cheese, Spring vegetable pistou, sauteed pea shoots, the toji’s favorite, prosciutto or jamon, or the local Shiga specialty and historic ancestor to sushi: rice-stuffed, sour-fermented freshwater fish…

Stats

- Rice: Tamazakae (locally grown)

- Rice polishing ratio: 60%

- Other: Muroka (not charcoal fined), genshu (undiluted), namazake (unpasteurized)

- Yeast: 1401

- Acidity: 2, ABV: 17.5%