JUNE 24, Treasures from Okayama, Part 2: Gozenshu Bodaimoto Nigori

Gozenshu Bodaimoto Junmai Nigori Genshu

Talk to any sake nerd (Japan or US) about Okayama and they’ll mention two things: Omachi rice and Gozenshu. In Japan, industry nerds might exclaim “Tsuji-san!” or “Maiko-san!” in reverence for toji Maiko Tsuji, who has taken the Gozenshu Bodaimoto story to a global stage.

The Gozenshu Bodaimoto Story

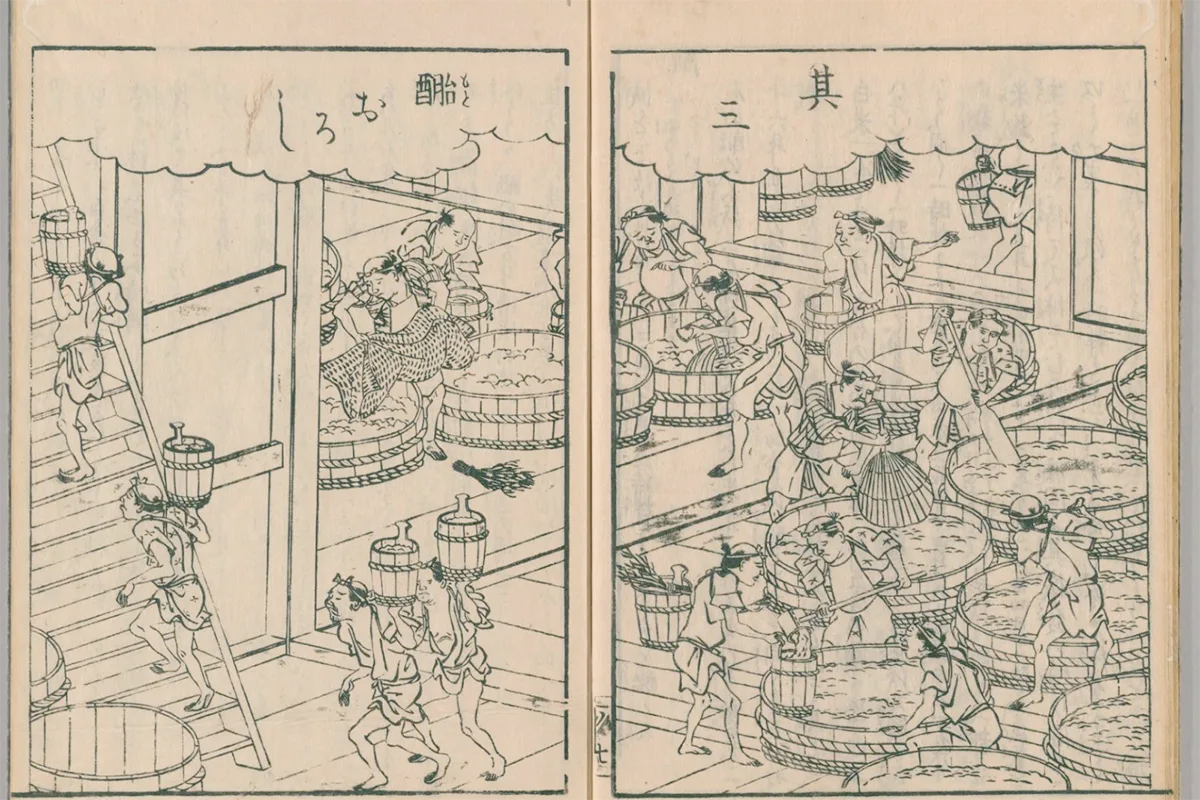

Gozenshu is one of the classic stories in sake brewing, and it would be ridiculous if it weren’t true. Essentially, the bodaimoto sake brewing method was developed by monks at Shoryakuji Temple in Nara prefecture as early as ~1300, based on methods that originated in China. Bodaimoto was perfected and utilized with regularity during the Muromachi period (1338)-- the oldest text describing bodaimoto (Goshu no Nikki) dates to 1355 (or 1489, no one is sure). The bodaimoto method was suited to late Summer/early Autumn brewing and involved soaking raw rice in water to create a sour water through the action of bacteria. The rice was strained out, and the sour water (good for saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, bad for undesirable wild yeasts/bacteria) was used as the basis for yeast cultivation and brewing.

Centuries later, new methods of brewing were developed. The Winter-suitable kimoto method, invented in Itami, Hyogo, rapidly grew in popularity near the beginning of the Edo period (late 1600s). Around this time, an edict was issued restricting sake brewing to the Winter months. Because of kimoto’s suitability to cold temperatures, before too long, all Japanese brewers switched to kimoto (or some other obscure methods). Bodaimoto– not suited to the cold– completely disappeared from the general sake brewing scene.

Enter London antiquities dealer Mike Deen. The year is 1984 and Mr. Deen has married one of the daughters of the Tsuji family, owners of Tsuji Honten, a sake brewery in mountainous, remote northern Okayama. In the course of his work, Deen came across an old book which clearly made reference to sake brewing techniques. Of course, he brought it to his extended family to share and deciphe

This book is the Nihon Sankai Meisan Zui (Illustrated Famous Products of Japan from the Mountains and Seas), and contains brewing techniques from 1799. Tsuji Honten’s toji at the time, Takumi Harada (Maiko Tsuji’s predecessor), had never heard of such a method. So he tried making it, and the result was (as expected now, with many versions of Bodaimoto on the market) sour. He thought it was spoiled, and people would never accept it. So Takumi set out to adapt the recipe to the taste preferences of the 1980s. He “repeatedly tried and tested the new "Bodaimoto" to create a method suitable for Tsuji Honten. A small amount of rice koji is soaked in water, lactic acid bacteria are allowed to grow, and "soyashi water" is made. When a large amount of lactic acid is produced, it is heated and sterilized once to increase safety before being used as brewing water.” The result was much less acidic (but still higher than most), with a soft roundness and dairy/lactic flavor profile. This would be the first Gozenshu Bodaimoto product: the one before you today, launched in 1986. “Because it incorporates natural lactic acid bacteria, it has a flavor similar to Calpis and a refreshing fruity aroma. In addition, while retaining the complex umami flavor, the acidity gives it a clean aftertaste…There are many rare sakes, but there are not many that are rare, delicious, and can be drunk in large quantities. Gozenshu's "Bodaimoto" is the latter.” (https://www.gozenshu.co.jp/topics/bodaimoto.html)

Toji Maiko Tsuji has transitioned the brewery entirely to this method as of 2024, making it the only bodaimoto-only brewery in the world. On top of that, as of 2023, Gozenshu is committed to brewing exclusively with Okayama Omachi rice.

Thanks, Mike Deen!

Omachi

I discussed the heirloom sake rice grain Omachi in depth in last January’s club writeup (which is on the Sunflower Club Archives page). Back then, I introduced Sakura Muromachi’s “Bizen Maboroshi” Junmai Ginjo Omachi sake, arguably the #1 OG Omachi sake in the US (and, I believe, the only other sake brewery in Japan exclusively using Omachi rice). Okayama sake has a deep relationship with Omachi: 90% is grown in Okayama, and it is second only to Yamadanishiki (very close, too) as the sake rice grown. Omachi was discovered and bred in Okayama in 1859, and much like Bodaimoto it was lost to time when “superior” rice varieties were introduced. Omachi was ‘rediscovered’ in the late 80s/early 90s, and it remains expensive, difficult to grow, and very fussy to brew with. And yet, it is the beloved heritage of Okayama and the exclusive rice of Gozenshu.

So I’m going to skip the full Omachi spiel and talk just a little bit about Gozenshu’s unique relationship with Omachi. (And I apologize for the low resolution on the image– I captured this screenshot from a zoom presentation with the brewery, much like the rest of these!)

Gozenshu sources Omachi from farmers in the 7 growing areas notated on the right. What this illustrates is Gozenshu’s strong connection to the source of their rice, even if they don’t endeavor to cultivate it themselves. Much like a winery working with a range of different growers and sources, getting to know each one and bottling them separately, Gozenshu is working to understand and appreciate each source of Omachi rice, each batch, and its best application.

First, the “worst” Omachi rice, or the lowest grade rice according to the system discussed with Marumoto Shuzo: Tougai, ungraded. Tougaimai is theoretically subject to no requirements on grain size, ‘neatness’ of grain, green grains, or the presence of dead rice or foreign matter. So it could be really bad rice. But as Maiko Tsuji explained in this presentation, ungraded doesn’t necessarily mean it’s under this low bar. There are many other reasons a rice might end up tougai, including the location of the field, whether the farmer used certified seed, selling it without inspection. Maiko Tsuji felt an obligation to make good use of this rice which might otherwise go to waste, and produce a dignified product with strong demand and a high cost performance. So she took advantage of the low ingredient cost, polished the rice to daiginjo level (50%), and produced a fruity, fresh, unpasteurized style that brings pride to the fact that the rice and resulting sake is high quality despite its ‘low’ grade. This product doesn’t make it to the US, but it’s a really fun one to enjoy in Japan (mostly just Okayama, as it is in high demand and sells out quickly!)

On the other side of the coin, Maiko is working to advance the highest potential of Omachi rice. Tokujo is the highest grade of sake rice, and as you learned it’s based on size, consistency of grains, and so on. Th Tokujo rating however is really only discussed or marketed in relation to Yamadanishiki, specifically Hyogo Yamadanishiki. In addition, the price of sake is directly correlated to the polishing ratio, with the most expensive sake on the market being polished to 35%, 15%, 7%, etc. To Maiko, this feels like a lost opportunity that misses the point of Omachi’s potential. So she envisioned a top–end product that sets the bar even higher than Tokujo grade, and uses this rarity– such rice is extremely rare– as the basis for the sake’s value, rather than some arbitrarily excessive rice polishing ratio. Her belief is that if the bar (and reward) are high, it will encourage farmers to reach higher, and it will carve out a place for humble heirloom omachi among the most valuable, coveted sake in Japan.

Last Fall I had the opportunity to preorder this Tokujo Omachi, but having never tried it before, and the price being SO high (~$500 wholesale!) I was uncomfortable drafting an offer for customers blind. So I took the dive on one bottle and decided that if it didn’t sell (it didn’t), we would open it to celebrate the end of Fuyu Fest with our team.

I was on an emotional high that night, so it’s hard to say that my assessments were accurate or that I was in any place to take notes and remember. But if you’ve ever had Kuheiji Kyou Den Omachi it’s similarly beautiful and structured, with bright acidity and a light petillance. Delicate woodsy, herbaceous notes interweave with stonefruit, the familiar calpis/lactic brightness, with a gorgeous, long finish. The length and delicacy of Zankyou 7, the complexity and Omachi-ness of Kyou Den, and the unreasonably gorgeous cedar box of…well, I’ve never seen such a pretty box. I have it in the shop, if you want to see it. I can’t bear to get rid of it!

Service & Pairing

If you’ve had this sake before, it’s quite possible you’ll feel you’ve never had this sake before.

Gozenshu nigori changes so much over the first 12 months, it can be unrecognizable from one bottle to the next. Within the first 6 months of bottling– we’re there now, on this just-landed fresh version (2024 bottling)– you can really taste the herbaceous, minty, zingy, balsa-wood notes of the Omachi. At around 12 months it gets rounder, softer, the yogurty tart lactic notes turn to buttermilk and soft cream, it takes on a sasparilla/cola/vanilla quality and the omachi becomes its deep velvety self. After 3-4 years it really starts to take on a bit of color and gets very indulgent, really wonderful served hot. In the Sunflower cellar, I have about a case from 2021 resting and waiting.

But at this stage– fresh and young– I LOVE it with one salad in particular, and I’ll share it with you. This might have been the first time I created an “OMG” sake pairing moment at home, ever. I call it Gozenshu Salad and you can only really make it in Spring-Summer when the ingredients are seasonal and the gozenshu is fresh.

Gozenshu Salad

- 1 medium persian or japanese variety of cucumber, seedless, large dice

- 8 oz cherry tomatoes, halved

- 1 large avocado, large dice

- 2 oz good feta cheese in brine (preferably french or greek), crumbled (optional but great)

- 2 T minced fresh dill

- 1 T minced fresh parsley

- Juice of ½ a juicy lemon

- Good glug of grassy extra virgin olive oil

- Salt to taste

Before prepping everything else, dice the cukes and toss them with a few pinches of salt, placing them in a colander over a bowl in the fridge to drain some of the liquid. In the meantime, prep the rest of your ingredients.

Toss everything but the avocado and oil together. Once nicely incorporated, add the avocado, a good glug (1-2 T) of olive oil and gently toss once more (do the avo last so it doesn’t accidentally mush up). Taste for seasoning and adjust acidity and salt as you wish. Serve with a nice tall glass of Gozenshu. Grill some salmon to make it a meal.

Stats

- Location: Okayama (North)

- Rice: Omachi

- Polishing: 58% (koji) 65% (kakemai)

- Yeast: #901

- SMV: -6, Acidity: 2.2, Amino acids: 1.7

- Starter: bodaimoto-inspired, sashimoto pied de cuvee

- Press: Yabuta, with lees reintegrated for nigori